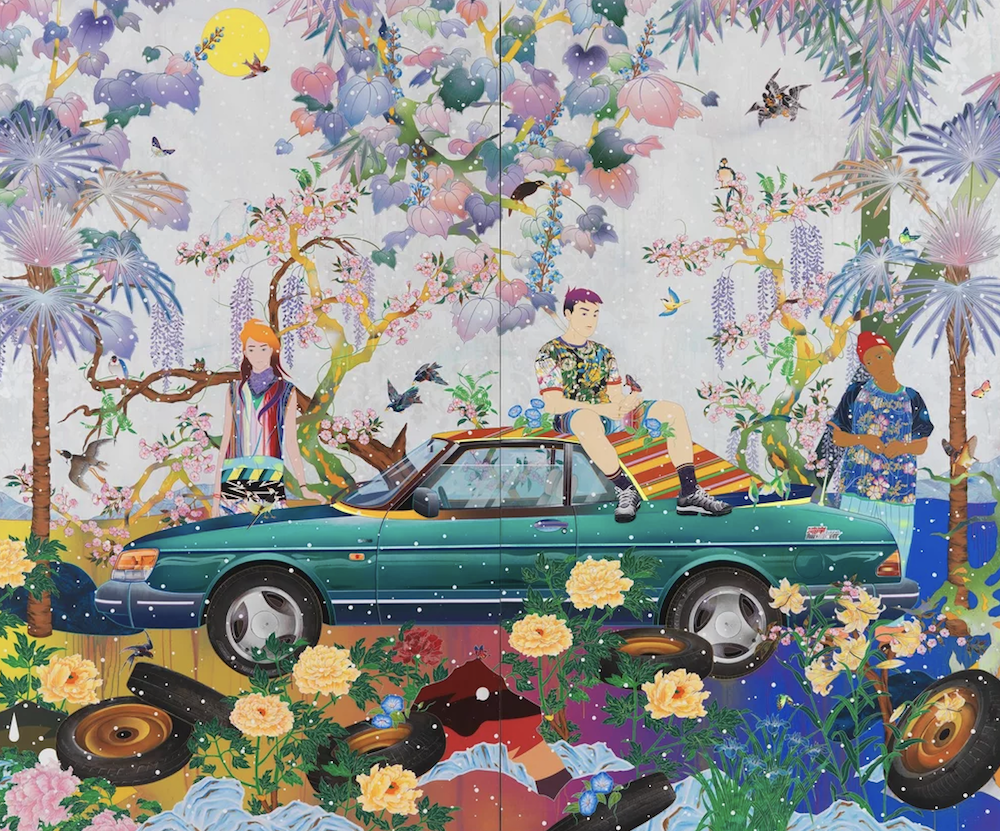

If you could read a pattern like a page in a book, the intricate textiles and wallpapers in Tomokazu Matsuyama’s paintings would speak volumes. Colourful motifs crowd the dense, graphical surfaces of his works, forming garden vistas or intimate boudoirs. Their origins are eclectic: a luscious floral might be drawn from a print by 19th century British designer William Morris or from an Edo Period kimono. In a bed of plants from divergent climes, an empty Sapporo bottle and a Starburst wrapper lie like the detritus of globalisation. A portrait inspired by a photograph of French couturier Christian Dior, meanwhile, bears the golden flourishes of a counterfeit Hermes scarf that Matsuyama bought in New York’s garment district. Completed on dynamically shaped canvases, these paintings take their compositional cues from Grand Manner portraits or pastorals in the pre-modern European tradition, while their use of skewed perspectives and absence of shading recall the flat planes of Japanese woodblock prints known as ukiyo-e. Signifiers of East and West are willfully scrambled here, as are renditions of the ‘real’ and the ‘fake.’ In Matsuyama’s work, as with his own diasporic identity, such differences are shaky social constructions.

Matsuyama was born in Takayama, Japan and moved to New York in 2000 at age 25. In the Big Apple, he encountered the work of street artists like Keith Haring and enrolled at Pratt Institute to study graphic design. This may explain the graphic quality of his paintings – at least as much as the influence of the Japanese pictorial tradition. At the time, he had few venues to exhibit his self-taught work save the bare walls of industrial buildings along the Brooklyn waterfront, including in Greenpoint, where his studio remains today. The language of street art was stylistically formative, but it also shaped Matsuyama's commitment to the public realm.

The 2000s were a time when Japanese art movements such as Simulationism and Superflat achieved global recognition, and Matsuyama was often confronted by the expectation that he deliver a recognisably anime-indebted style. Refusing to be reduced to cultural stereotypes, he chose instead to subvert them: the imagery in his work, then and now, filters influences from European and American art history through Japan and back again, so their origins can be difficult to pin down. Collaging elements from fashion and home décor magazines into compositions derived from the Western canon, he then adds layers of patterns from a wide range of sources – many of them drawn from his personal archive of historical textiles – that act as a kind of dazzle camouflage. Cloaked in these designs, his alluringly inexpressive figures withhold plenty of secrets.

When it comes to patterns, hardened notions of ownership and appropriation have been obsolete since at least the 16th century, when Dutch traders brought wax prints to West Africa, Polynesia, and Japan. In our era of heightened international trade and digital information exchange, cultural sampling occurs at an ever-increasing rate. Matsuyama’s own dialogue between East and West recalls the transformational influence of ukiyo-e on European Impressionism by tracing their journey in reverse. The result is a syncretism that speaks to Matsuyama’s own trajectory as a global citizen and, in turn, embodies the postmodern condition.

Over the past several years, Matsuyama has expanded his engagement with public space by developing his graphical universe in three dimensions. Major sculptural commissions, including works for New York’s Madison Square Park and Tokyo’s Shinjuku Station, realize the contour lines of his paintings in mirror-polished stainless steel. Each plane is torqued on an axis, so the subjects rendered have a sense of continuous motion. As one circumnavigates their mirrored surfaces, struggling to assemble their constituent parts, the reflected environs further resist the logic of the eye. These sculptures are anti-monuments, perfectly suited for an age when statues around the world are being pulled off their plinths.

Like his paintings, Matsuyama’s sculptures also refuse to adhere to any one narrative. The patterns that inform their steel armatures, and which are sometimes powder-coated along their edges, are designed to keep us guessing. After all, identity is itself a kind of a pattern language – an accumulation of gestures and appearances that society trains us to recognize. If we resist such reductive readings of race and culture, Matusyama reminds us, we will instead see the world for all its dazzling complexity. — Evan Moffitt, writer, editor and critic

https://www.alminerech.com/