Since moving to the United States at thirteen, Bony Ramirez has never returned to the Dominican Republic. He owns no photographs of his childhood there but has vivid impressions of its colors and textures. Today, living in Harlem and working in Jersey City, Ramirez celebrates Caribbean culture through paintings and sculptures of these reconstructed memories. Listen to the Radio Juxtapoz podcast with Bony, below, from a few years ago.

Ramirez’s work is populated by a taxonomy of symbols and motifs that seeks to broaden the understanding of Caribbean history, culture and traditions. Seashells, coconuts, machetes, horns, wood, chains and hardware materials are signifiers used to grasp the Caribbean’s cultural complexities, colonial history and the toughness that lies beneath its paradisiac surface. Ramirez resorts to magical realism to keep his childhood memories alive, a strategy that he connects to the experience of Caribbean immigrants growing up in the United States.

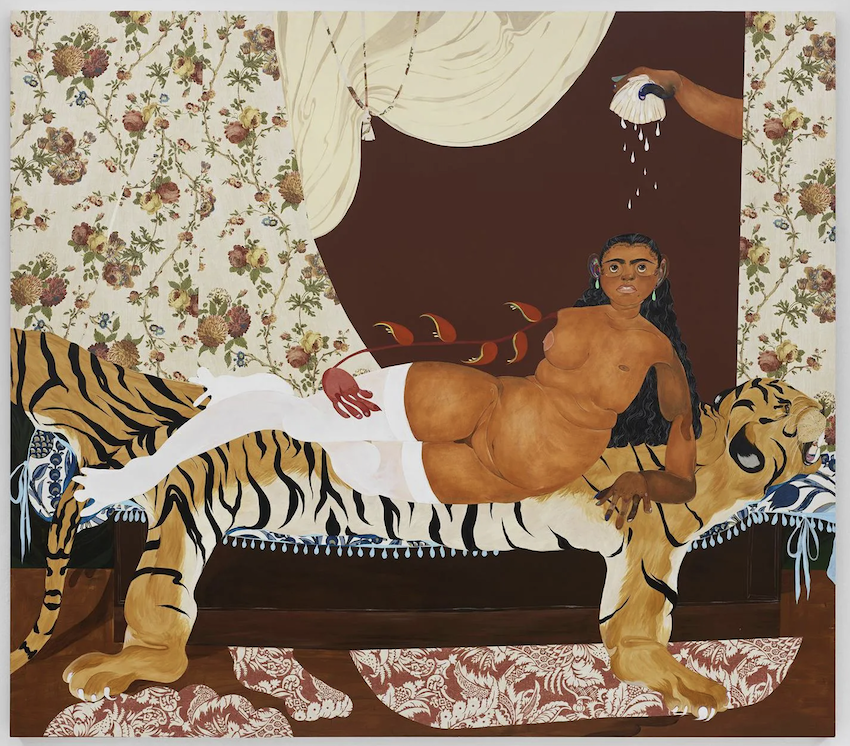

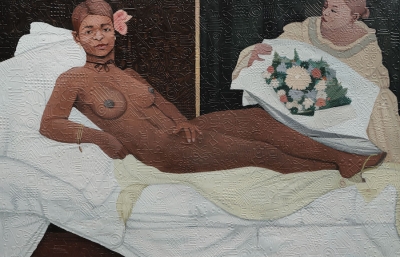

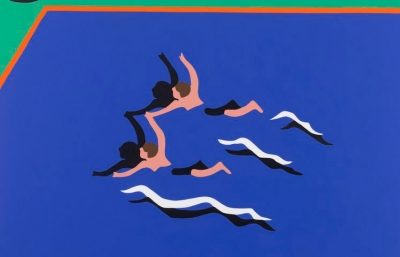

In TROPICAL APEX, Ramirez combines his childhood memories and imagination in a series of portraits. At times referencing familiar places, like the family-run bodega and the kitchen of his rural childhood home, the paintings portray fictional characters belonging to a larger narrative. These figures are Black and brown subjects whose bodies present exaggerated features: endearing doll-like eyes and anatomical caprices that evoke themes and motifs of the Caribbean natural landscape. Despite their unusuality, these portraits recall Mannerist portraiture. They exude royal power and beauty. Ramirez also cites Pablo Picasso, Francis Bacon and Surrealist artists as his inspiration. “These figures are not human per se, but they are not non-human,” says the artist.

Ramirez realized his paintings with a signature mixed-media technique. He develops the figures separately on paper in colored pencils, oil pastels and acrylic wash. The cut-out is then applied to wood panels worked with acrylic and embellished with other three-dimensional elements. He often utilizes European wallpapers to address the colonial history of the Caribbean.

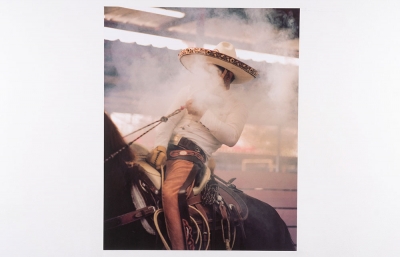

A proudly self-taught artist, Ramirez points to his background in construction as a source of his ingenuity. His attention to tactility expands beyond the paintings. The exhibition includes sculptures and installation elements realized in a style that recalls the colored hardwood architecture of the Caribbean. On the mezzanine, the artist recreates a rooster fighting ring like the one his father had constructed in their backyard in the Dominican Republic. The artist never appreciated this cruel hobby, a popular sport in his birth country, but is interested in exploring its cultural ramifications and roots in the definition of Caribbean masculinity.

Lastly, a series of constructed sculptures populate the central area of the gallery. Realized with taxidermy animals and several other materials encountered in his paintings, these works are self-portraits that recount personal stories. “They help me understand aspects of my life,” says Ramirez.