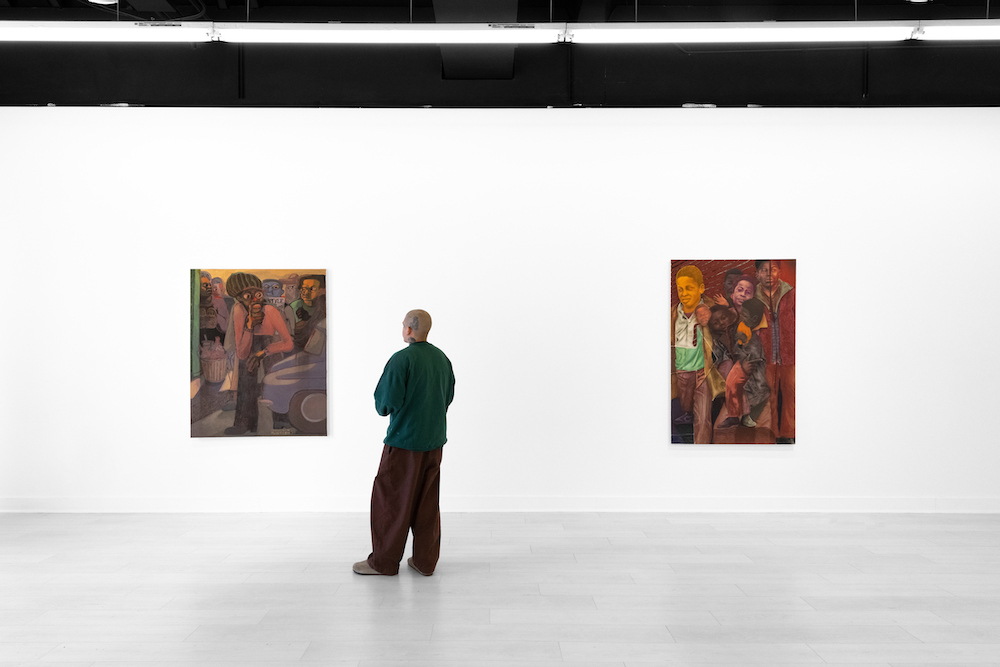

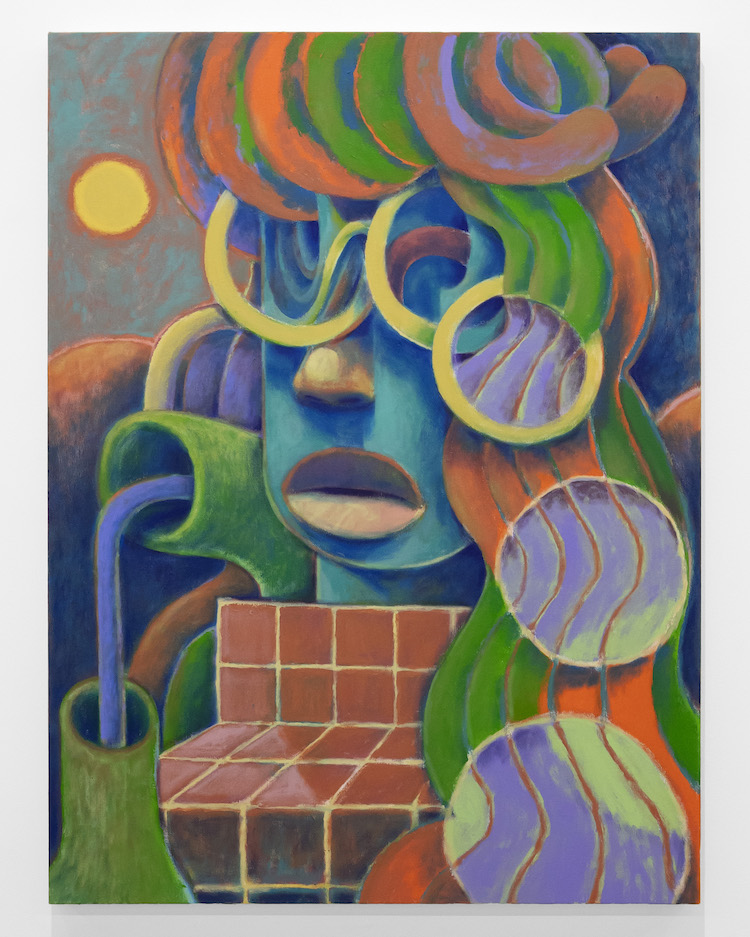

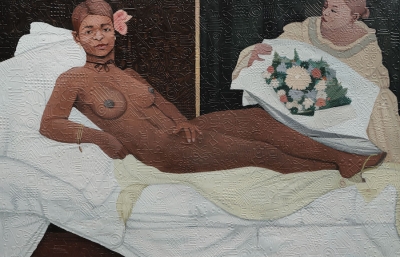

pt.2 Gallery's latest exhibition centers around figuration featuring new work by Molly Bounds, Liz Hernández, Lynnea Holland Weiss, Wardell McNeal, Cinque Mubarak, Héctor Muñoz-Guzmán, Landon Pointer, Lenworth McIntosh, Hana Ward and Woodrow White. Spanning mediums, styles and modes of representation, the exhibition highlights the body in all its multiplicities and complexities. From Mubarak’s photographs which focus as much on the subjects within them as the places in which they were created, to the loose figuration of Hana Ward and Lynnea Holland Weiss which pulse with emotion. From the works of Héctor Muñoz-Guzmán, Wardell McNeal and Lenworth McIntosh, all who use an element of drawing or cartooning to hint at larger personal and social issues, contrasting these with the tighter works of Molly Bounds which freeze a moment in time in quiet rapt focus. From Liz Hernández’s brass bodily relief which emanates with shamanic resonance, to the mixed styles and figurative approaches of Landon Pointer, to Woodrow White’s comedic scenes which pull from art history–the artist’s within this group show utilize the body as a site for investigation, recognition and mediation.

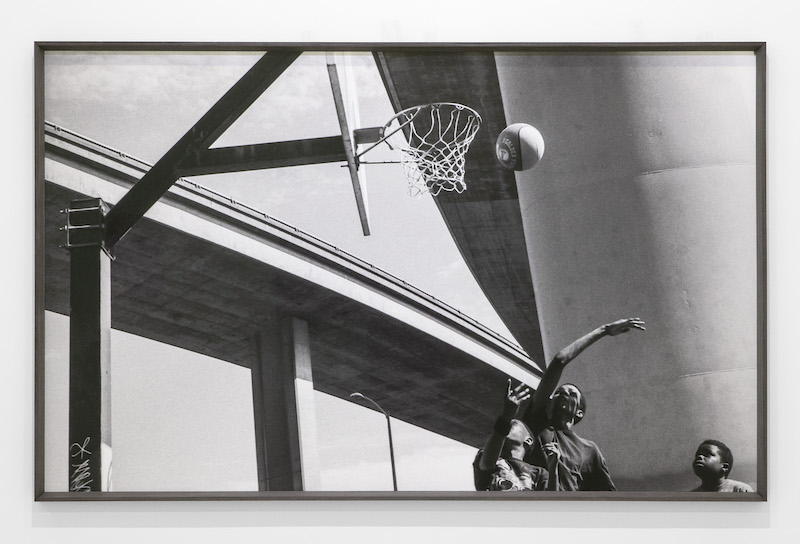

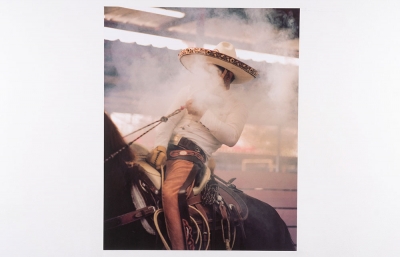

As the exhibition’s lone photographer, Mubarak uses photography as a way to excavate familial histories, as a means of documentation and self-discovery and as a tool for self-love and healing. Two 35mm photographs grace this exhibition, a dramatic view of children playing basketball beneath a swooping underpass in “34th&mlk”, and a wide view composite image of a woman confidently staring back at the viewer from the back of a pickup which blends into the shadowed profile of a figure from the back, afro pick set like a clock hand at 11, merging into telephone wires that lead to the bottom left of the composition, a heart floating above the wires left by the smoke of an airplane trail. The title “Town Luv” speaks to the artist’s rootedness within his hometown of Oakland, and the images resonate as much as records of people in time and place as they are a love letter to the community and place that has raised the artist.

Contrasting these photographs is Liz Hernández’s human scale composition of a woman’s body, constructed from five sections of brass. Titled ”Zurcido Espiritual” or spiritual mending, The framed figure is set in profile, eyes focused downward on her hands which hold a sewing needle, small marks denoting thread covering different parts of the figure’s body. The artist’s fluid line drawings beautifully translate as embossed marks on brass, a brushy patina providing further textural embellishment. The work feels both immediate and folkloric, both fresh and eternal, and incredibly personal and deeply universal.

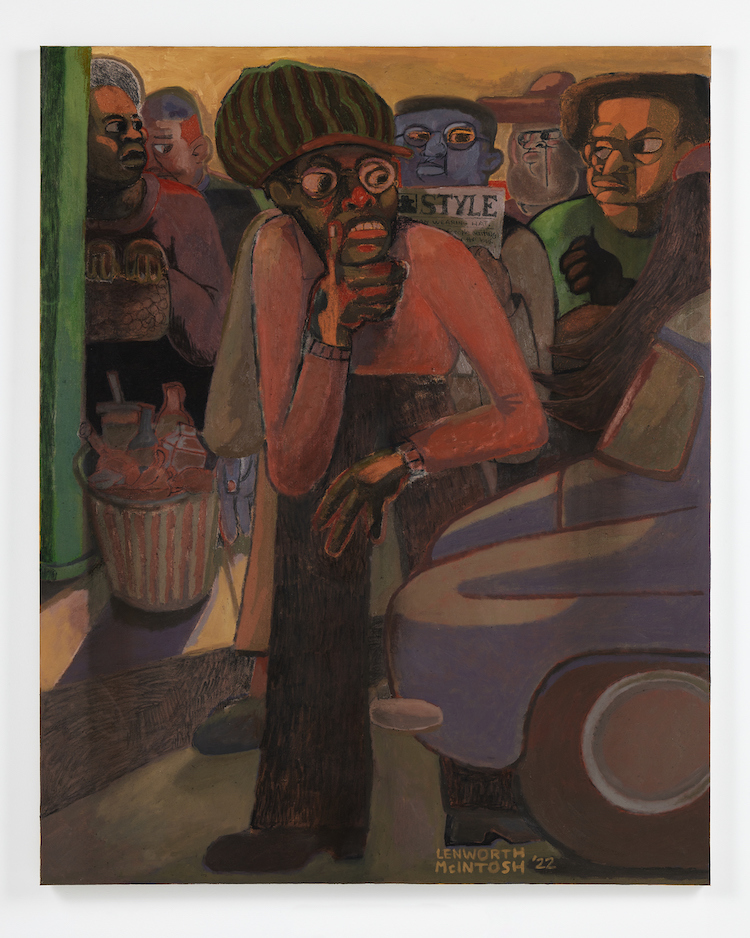

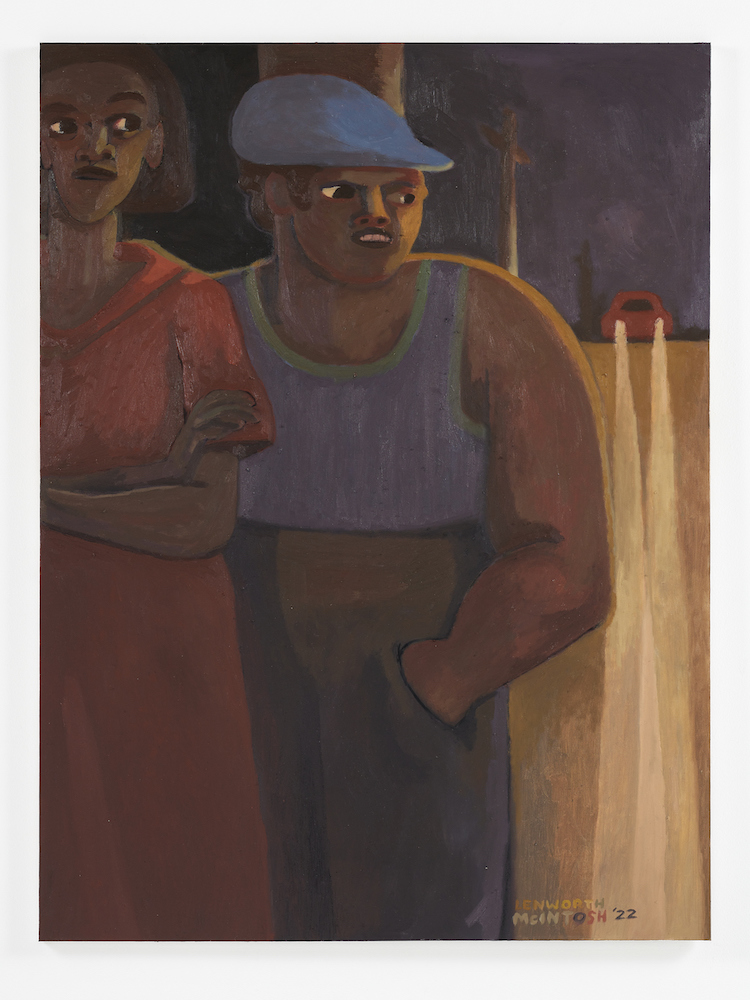

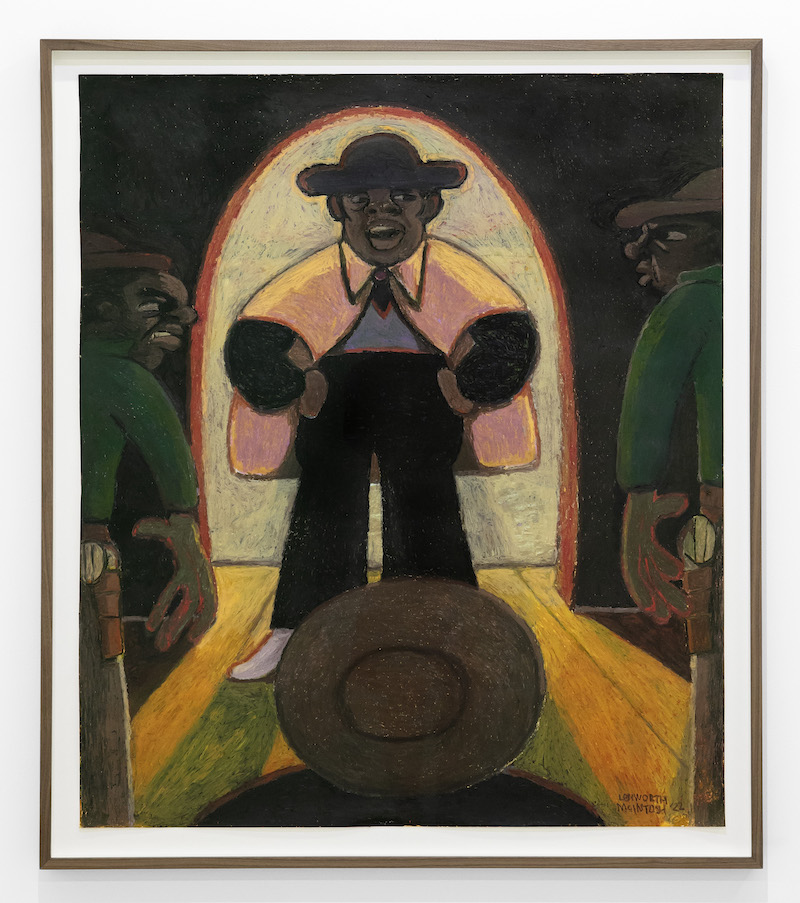

The works of Lenworth McIntosh, Héctor Muñoz-Guzmán and Wardell McNeal all succeed and are united in breaking down the self through means of drawing, exaggeration and graphic figuration. McIntosh’s works on canvas and paper use a variety of drawing and painting materials to create dynamic scenes of urban life. The artist’s largest work ”New York, 1972” sees a variety of characters set within a busy composition, one figure crossing the street looks to the right of the canvas, with the eyes of five different figures in the background each looking towards a different area, a permeating sense of tension and distrust dominates, the masterful colorwork and personality of each character keeps the viewer entranced within these complicated dynamics.

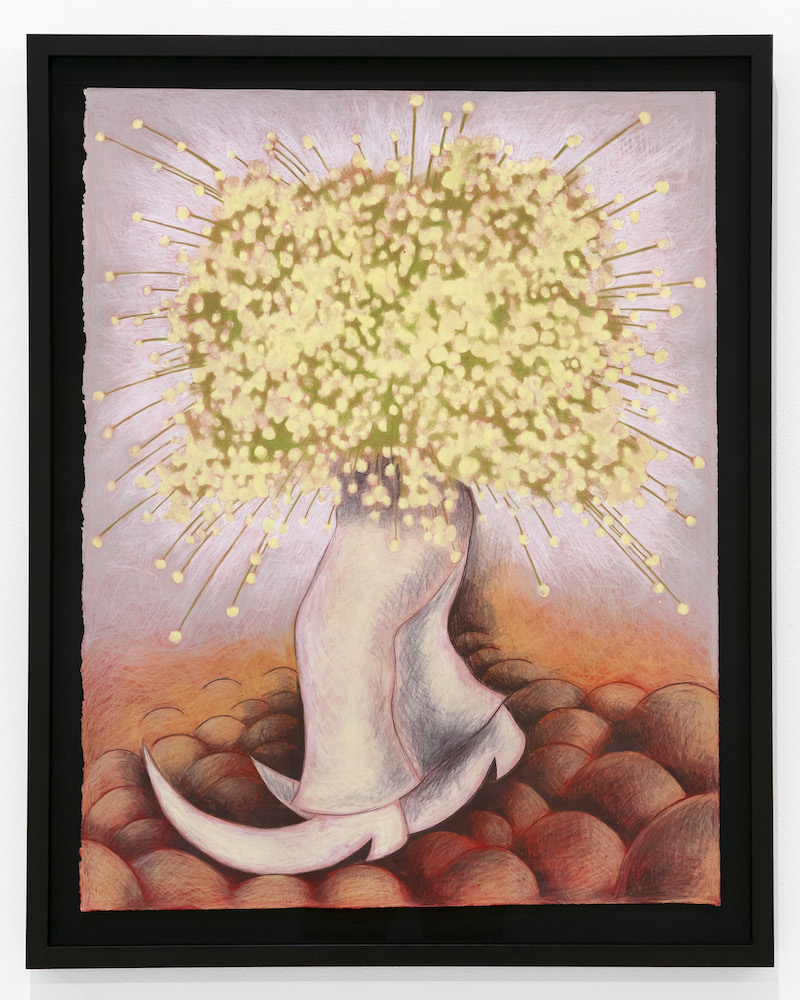

Relating to these works is a single piece by Héctor Muñoz-Guzmán titled “Vendedor Vaquero (Cowboy Salesman)”. The drawing on paper is perhaps the most surreal piece from the show, a cowboy with elongated pointy boots dances upon a cloudy surface with such fervor that his upper body has become entirely enveloped by a yellowish-green firework bloom. Much like McIntosh’s works, this work by Muñoz-Guzmán is deeply alluring through the artist’s beautiful mark-making as it combines with an entirely confounding narrative that unexpectedly immerses the viewer.

The loose figurative works of Los Angeles-based artist Hana Ward employ a mixture of realism and more illustrative elements. The artist’s lone work feels at first like a quiet composition, a seated figure dominates much of the bottom half of the composition, hand on a royal blue table, while a cat sits quietly above the figure’s right shoulder. Yet the mixture of the figure’s intense yet unknowable gaze, and the artist’s brilliant color choices, bright pink walls and a deep maroon carpet only add to the painting’s hard to place emotional timbre, leaving viewers to wonder what dynamics are at play that we don’t understand.

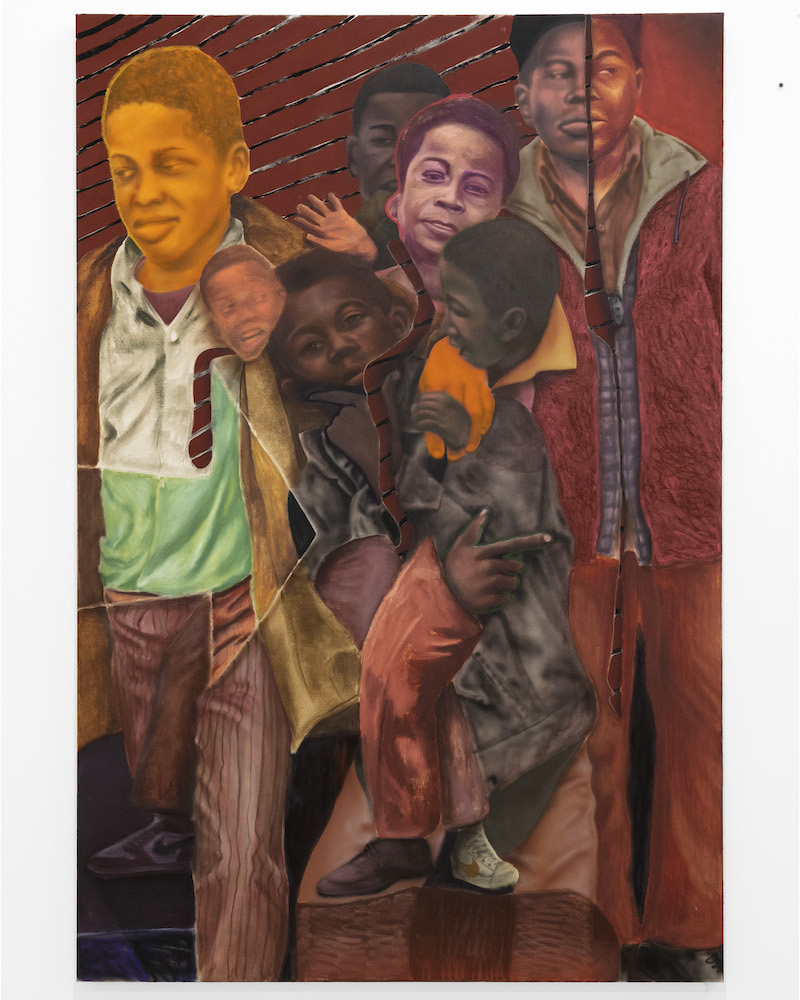

In a similar vein, Oakland-based painter Landon Pointer employs a voracious appetite for techniques, often utilizing different means of image-making within the same work, creating deeply layered paintings that call forth issues surrounding memory, childhood and identity. The artist’s largest work within the show, “Crossed the Bridge” sees a collision of seven figures set against a brick red backdrop. Each figure feels superimposed over the other yet all are simultaneously in conversation, with varying scales, hues and means of painting furthering the collision of elements. At times the background cuts right through a figure, reimposing itself within the conversation, hinting at a kind of loss, yet the painting still emanates a warmth as we meditate on our own childhoods and the sense of innocence that we can never truly regain from those times.

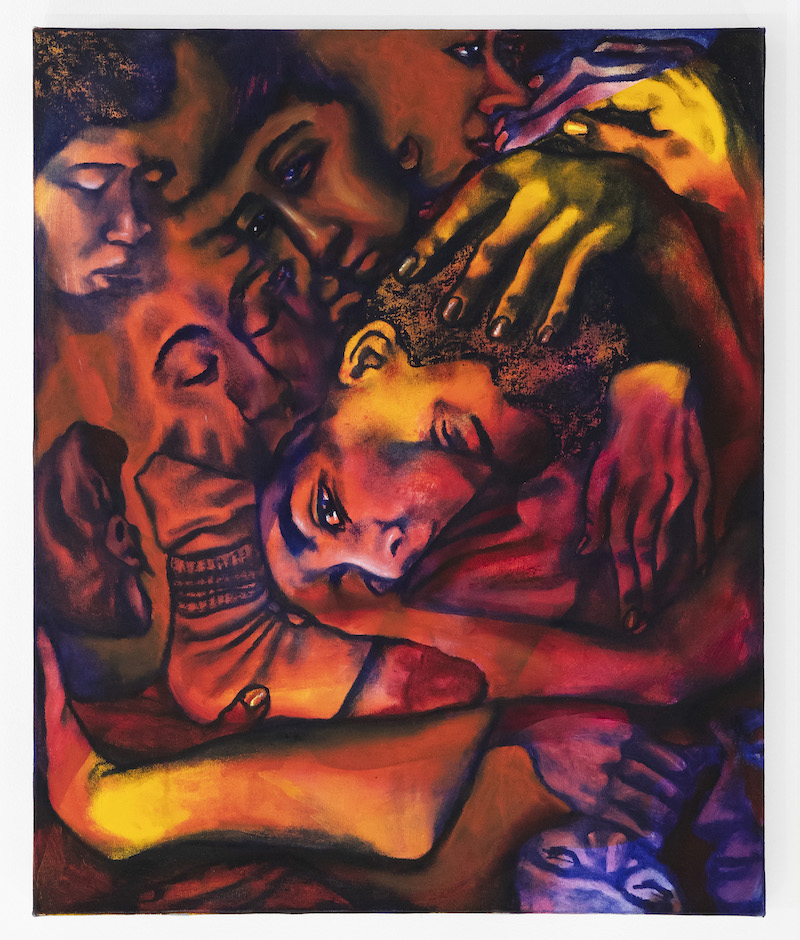

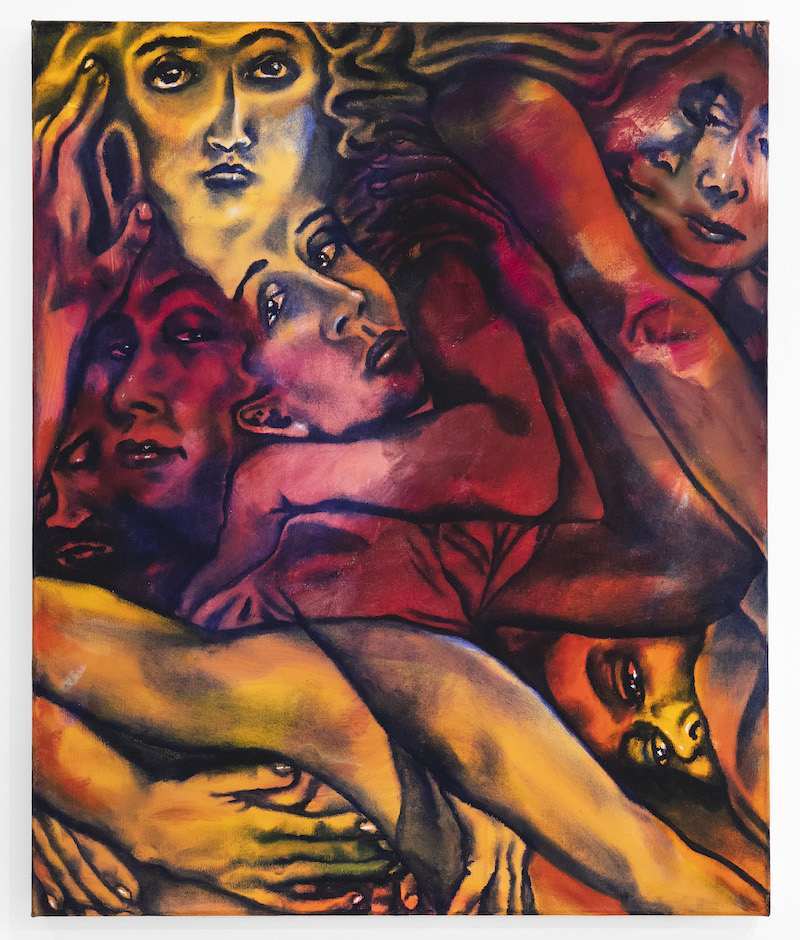

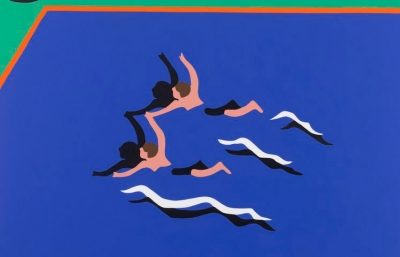

Los Angeles-based artist Lynnea Holland Weiss’s work also features a mashup of figures, the delineations of bodies left unclear as limbs merge into faces and trailing hair is bisected by a foot. With titles such as “Bruised Peach” and “Sunset Squeeze”, the works are primarily painted in dark tones over a warm reddish and orange variegated background. Weiss’s figures are either turned outward towards the viewer or inward in a seeming embrace of the amorphous surrounding figures, allegories for the embrace of community and our interconnectedness with one another.

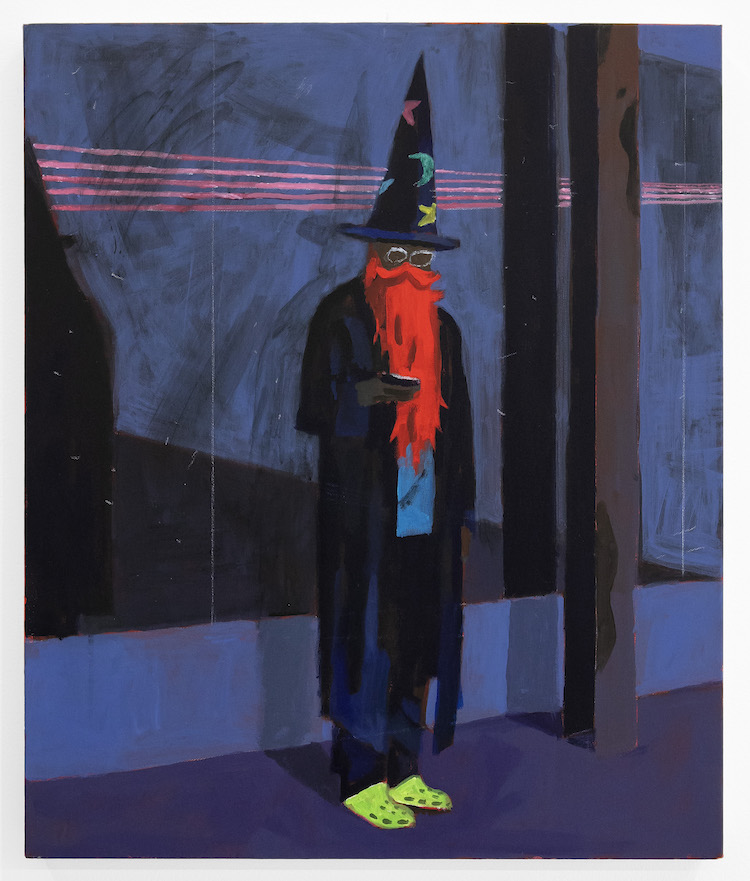

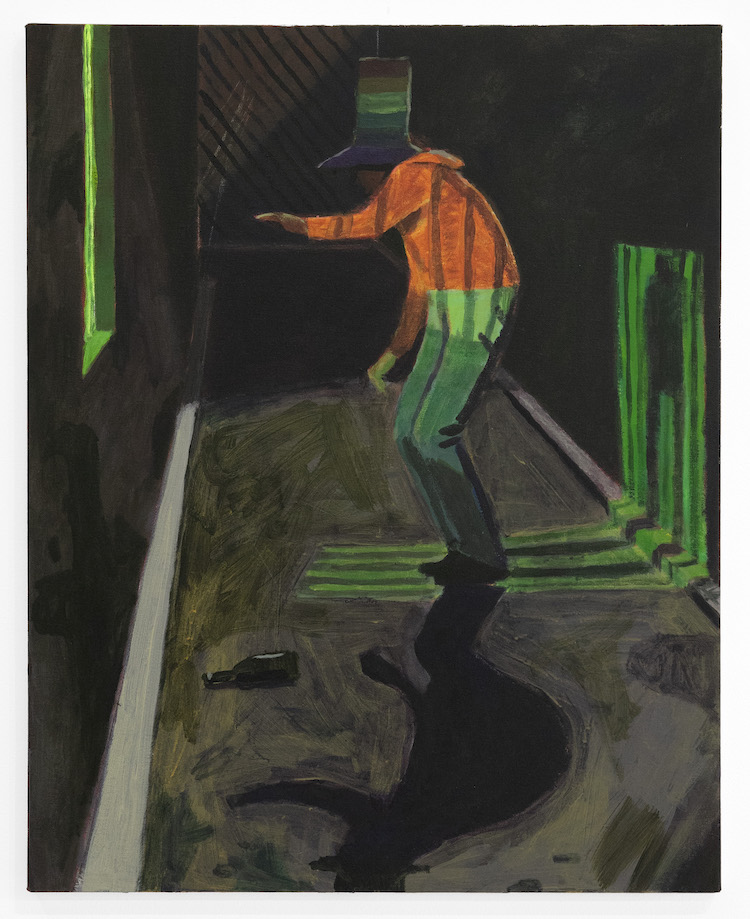

Diverging from the collision of bodies seen in Pointer and Holland Weiss’s works are the paintings of Woodrow White and Molly Bounds. White’s paintings are focused on lone figures set within space, whether it’s a drunk reveler in “Sorted” who seems to be the only one left at a party in a dark alley, or the more contemplative bearded, wizard hat and cloaked individual sporting fluorescent crocs who seems to be consumed by his phone potentially waiting for a rideshare to show up. The latter painting was partially inspired by Manet’s “The Absinthe Drinker” which similarly depicts an individual so consumed by a dark-hearted revelry that they’ve been left to wallow in their own stuporous condition long after everyone else has left.

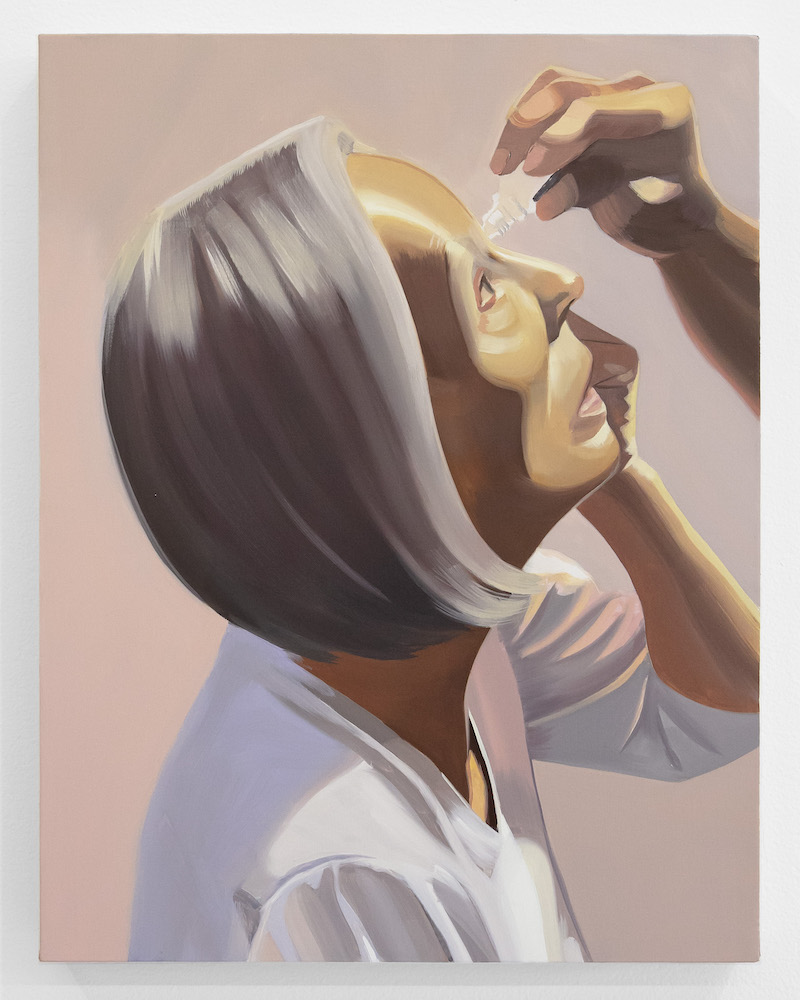

The works of Molly Bounds similar to those of Woodrow White, center a solitary figure within both compositions. With clean blends of color and fluid strokes of oil paint, Bounds builds a mood within each work that is inseparable from the more palpable content contained within. With a coolness and singular focus, the figures within Bounds’ works are lost within the moment, the act of capturing said moment in oil paint only furthering the sense of quiet contemplation in which we find the painting’s subject, fostering a similar sense of introspection within the viewer.